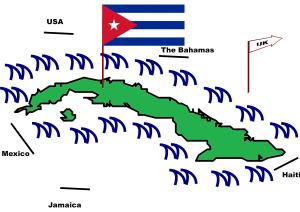

Cuba

February 2, 2011 § 1 Comment

Who lives there?: Slightly more than 11 million people. The demographic mix is typical of the Spanish Caribbean: 65% white, 25% Mullato, 10% black. Almost everyone speaks Spanish whilst some of the black community speak Haitian Creole, and the Yoruban language Lucumi is used a liturgical language amongst practitioners of Santeria.

Who lives there?: Slightly more than 11 million people. The demographic mix is typical of the Spanish Caribbean: 65% white, 25% Mullato, 10% black. Almost everyone speaks Spanish whilst some of the black community speak Haitian Creole, and the Yoruban language Lucumi is used a liturgical language amongst practitioners of Santeria.

There is roughly a 60/40 Atheist to Catholic split but it is also believed Santeria is widely practised syncretically.

There are also small but noticeable minorities of Chinese, Sephardic Jews, and Jehovah’s witnesses.

There are currently around a million Cubans (equivalent to 10% of the population) living in exile in the USA.

How does the system work? (the theory): I’m grateful to a friend who is an expert on the subject for explaining the system to me.

Cuba is a one party state. It legalised the existence of other parties in 1992, and other parties are allowed to organise in private and can even stand for elections in a personal capacity. But the Communist Party is officially the “leading force of society and of the state”. All elections are non party political and campaigning on a party platform of any kind is forbidden.

Within that framework there is a vibrant bottom-up form of indirect representation which forms both the legislative and the executive.. Each ward of 800 or so people elects a representative to municipal committees, and anyone who can gather a following at a public meeting is entitled to generous state support for their election campaign. These representatives are elected by two-round first past the post. Each municipal committee acts as the executive for its local area: the municipality, of whom there are 169. Terms are for two and a half years

Then there are 15 provinces each of which have a Provincial Assembly and there is a national assembly called the National Assembly of People’s Power. Terms here are for five years. The former acts as the executive for provincial government whilst the latter is the national legislative.

Both are elected in the same way: Deputies are indirectly elected by the municipal authorities who elect one deputy for every 20,000 residents they represent (rounding up) – again by two round FPTP. Each individual vacancy is dealt with in turn (so if a seat has two vacancies, candidates who are unsuccessful in the election to the first vacancy can stand for the second and so forth). The number of deputies elected this way, must by law, be above 50% and is normally just over 50%. The remaining seats are divided up amongst “nominating assemblies”. These groups comprise pressure groups for workers, youth, women, students and farmers as well as members of the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (of which more in a second). A body set up by the President – the National Candidate’s Commission – decides which of these organisations gets to nominate candidates and how many each. The NCC also has the final say on the election of any deputy and can demand a replacement if the successful candidate is judged to be inadequate “taking into account criteria such as candidates’ merit, patriotism, ethical values and revolutionary history”.

Up until this stage the deputies are only officially “candidates”. They then stand for election in a first past the post election with universal suffrage for the 618 seats into which Cuba is divided. However as there is only one candidate per seat this stage is entirely symbolic.

As well as forming the legislative, the National Assembly of People’s Power elect the executive (a President, a Prime Minister and a cabinet of thirty) and all the institutions of state (the judiciary, the supreme court, and the various state committees). However the y only meet twice a year, and in the meantime Cabinet – under the guidance of the President – act as a legislative body.

In parallel to all this exist the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution. They are somewhere in between the neighbourhood watch and the Stasi and might be the scariest thing I have ever come across. To quote Castro it is “a collective system of revolutionary vigilance” to report “Who lives on every block? What does each do? What relations does each have with tyrants? To what is each dedicated? In what activities is each involved? And, with whom does each meet?” It is a task of the CDR to keep a file on every resident. It also acts as a local community support group or residents association, and also as a neighbourhood watch. And as discussed it has a role in elections. It is estimated that nearly 9 million Cubans (90% of the population) are active members of CDRs.

In theory there is also an element of direct democracy in the Cuban system. If 10,000 signatures of eligible voters are recorded calling for a referendum on an issue then the referendum must happen. However this has only been tried once (or twice, depending how you look at it). In 2002 the Valera project (of which more later) collected 11,000 signatures calling for a national referendum on constitutional and political reforms. The Government’s response was to task the CDRs with gathering signatures for a counter-proposal that the constitution be made untouchable. They out-did themselves, indeed they rather over egged the pudding: they collected 8.1 million signatures – the signatures of 99.5% of all eligible voters.

How does the system work? (the practice): A question which has caused debate amongst political scientists for years is “is Cuba a democracy?” The case for the answer “no” is fairly obvious: clearly there is a communist party hegemony at the highest levels of government and the ban on political campaigning makes removing that hegemony an impossibility. Such is the hegemony that there is invariably only one candidate for President. The CDRs, media, and institutions of state also perform a powerful role in ensuring that the Castros and Communist ideology is never challenged. Moreover such democracy as there is, is indirect and partial – those nominated by external bodies and the National Candidate Committee’s final say on candidate suitability counting against it being a true democracy.

However, there are those that point out that saying Cuba is not a democracy isn’t really fair either – as it ignores the fact that policy making genuinely does involve the grass roots, that public engagement with the institutions of state is vibrant, and that the government does to a certain extent respond to the concerns of the people.

Personally I see this purely as a problem of semantics. It seems clear to me that there is absolutely no democracy at all in Cuba, but what there is is vibrant and effective community consultation and local engagement.

There are numerous reports of heavy handedness and human rights abuses by the authorities against those who refuse to recognise the exclusive legitimacy of Communism. There are also allegations that, whilst these things certainly happen, the lavish funding of exile and opposition groups means that these events are over-reported. In other words whilst Cuba is by no means the least repressive regime, it is by no means the most either – it just seems that way because we know so much about such acts as have taken place.

I’m in no place to judge on this so here are some facts: 75 dissidents (mostly journalists or members of Valeria) were rounded up in March of 2003 and given sentences of between 10 and 30 years for sedition; Reporters Without Borders consistently ranks Cuba amongst the least free countries in the world (it’s currently at an almost record lowest 13th, having been second only to North Korea at some stages); it is punishable by up to 20 years in prison to own books which teach about democracy or pamphlets advocating other forms of government; the total number of political prisoners is thought to be around 200.

How did we get here?: I’m putting quite a lot of history into this one because it is all relevant today (Cuban politics having been frozen in many ways for 50 odd years). Christopher Columbus landed in Cuba in 1492 (on his first voyage, although he had already been to the Bahamas by then) and, over the next few centuries, Spanish immigrants and their African slaves settled and wiped out the indigenous population.

Cuba was far happier with Spanish rule than most of its colonies in the region and it did not have its first rebellion until the 1868 “ten years war”. This was unsuccessful, as was the 1879 “little war” and agitation following the 1886 abolition of slavery.

Finally in 1895, under the leadership of José Martí and Máximo Gómez, Cuba rebelled for a final time. The rebellion was put down brutally and it is thought up to 400,000 people died in Spanish concentration camps. Martí himself died in the fighting, but not before he had built up considerable support from the USA (Martí had lived in New York for many years and was one of the few Cubans to be well known in the USA). Gómez meanwhile continued fighting a guerilla war.

In 1898 the USS Maine sailed to Cuba ostensibly to protect US citizens on the island but in what was widely perceived as literal gunboat diplomacy. It blew up unexpectedly in the middle of Havana harbour killing all 250 crew.

To this day it is not clear why the Maine blew up, it is now thought that it was a genuine accident – a result of heated coal dust getting into the gunpowder magazines – but there are many theories. The US public however were convinced it was an act of war by Spain and, spurred on by the “yellow journalism” of William Randolph Hearst, they demanded (and got) the Spanish American War.

The war took place between American and Spanish holdings all across the world, but it was in Cuba that it was the most fierce, with American troops fighting alongside Gómez’ rebels. The war only lasted a couple of months, and ended with Spain selling Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam to the USA for $20 million.

The four new areas were initially ruled as US dependencies (as two of them are to this day) but in 1902 Theodore Roosevelt (an old friend of Martí from his New York days) became President of the USA and granted Cuba independence. The USA was still designated as Cuba’s “protector” with “the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and to supervise its finances and foreign relations”. This state of affairs persisted until the communist revolution. At the same time it was agreed to lease a naval base (Guantánamo Bay) on the far eastern end of the island to the USA. This arrangement also remained until the revolution, at which point Cuba pulled out of it – the USA however refused to leave and continue to maintain a base there to this day.

The first few decades of Cuban independence were rocky with disputed elections, armed revolutions, and coups. When things got really rocky the USA imposed direct rule. The USA also maintained a strong, and some said stifling, industrial and trading presence. I’m cutting a lot out but if we jump forward to 1934 we see four governments falling violently in the space of a few months. The third of these was the Ramón Grau government which, whilst it only lasted 100 days, is still remembered as one of Cuba’s better governments – it introduced wide ranging social reforms which had a profound effect on the political landscape in that they gave Cubans a taste for left-wing policy.

The Fourth government of 1934 was the military dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. He was the head of the Army and he stepped in as the leader of a military coup. He ruled as a dictator for 6 years and called elections in 1940 which he won – ruling as President for a further four years. He then lost the 1944 elections to Grau.

Jumping forward to the 1952 elections and we find a three horse race in progress. In a clear first place was the left-wing (but strongly anti-Communist) Ortodoxos party, of which a young Fidel Castro was a member. They were led by the charismatic Eduardo Chibás. He vowed to end corruption and used his weekly radio show to campaign against it. In 1951, in the run up to the elections, he planned to get a number of senior congressmen to testify to the embezzlement of their colleagues live on air. When they pulled out at the last minute, Chibás instead committed suicide live on air by shooting himself in the head. He was replaced as a candidate by Roberto Agramonte and the Ortodoxos party surged in popularity.

Thought to be in second place was Grau’s Auténtico party (although he was not, on this occasion, the candidate). In a third, and rapidly becoming a distant third, was Batista. Realising he was going to get a pasting, Batista took matters into his own hands and staged a coup. In 1954 he staged elections which he won unopposed after the opposition pulled out claiming they were rigged. In 1956 the army staged a coup against Batista which he crushed. This confirmed the primacy of Batista’s rule, but also broke the back of the Army’s power.

Meanwhile in 1953, a small band of by-now communists led by Fidel Castro attempted to launch a violent rebellion. They attacked a barracks in Santiago in some force but the attack was a total washout. Most of the rebels were killed and Castro himself was arrested. He then made a name for himself at his trial – speaking without notes for four hours and ending with the famous phrase “history will absolve me”. He was released in 1955 as part of a general amnesty.

He regrouped his supporters in Mexico and in 1956 tried again: 86 of them landing from the yacht Granma. It was another disaster: most people were killed in the first engagement and fewer than 20 people survived the first night. Those that did were scattered in all directions. However a key group of four did manage to stick together and get to the hills safely: Fidel Castro, Raul Castro, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos.

Castro (left) and Cienfuegos playing for "the bearded ones" - a Cuban baseball team. Casro was a skilled pitcher who allegedly had trials for the Pittsburgh Pirates and Washington Senators. Some even claim he played in the MLB once for the latter but there's no evidence to back up the claim.

They built a strong following in the subsequent couple of years and by 1958 were leading a popular revolution that was sweeping the land. As anyone who has seen The Godfather: Part II can tell you, Batista fled Cuba at midnight on New Year’s Eve 1958, and the rebels entered Havana a week later.

Castro quickly became the major force in Cuban politics, and so implemented his strongly Russian vision for a communist state. His position, both personally and in terms of his politics, was cemented after the anti-Soviet Cienfuegos was killed in a plane crash in October of 1958, and after the classical Marxist, and occasional Trotskyist, Guevara left Cuba in 1965.

Castro became Prime Minister almost immediately whilst, after a series of interim Presidents, his close ally Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado was made President in July. This state of affairs continued until 1976 when, following a change in the constitution, Castro became President.

Not all of the rebels were communists but by 1960 the regime was heavily communist. Castro thus ruled in one form or another for 48 years, making him at the time he stepped down the longest serving world leader (if one doesn’t count either the largely constitutional monarchs Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand – 60 years at the time – and Elisabeth II of the UK – 52years at the time – or Saud bin Saqr al Qasimi who is the leader of Ras al-Khaimah which is one of the emirates that constitute the UAE – 58 years at the time). He stood down in favour of his brother Raul for health reasons in 2006.

The USA have made various controversial attempts to unseat him, inducing the disastrous 1961 military “Bay of Pigs” invasion, and various covert operations and assassination attempts collectively known as Operation Mongoose. However the regime was actually much more likely to fall as a result of the collapse of it’s sponsor, the Soviet Union, in 1990. This did in fact lead to the “Special Period in Time of Peace”: a period of economic austerity and hardship, rationing and also liberalisation as Cuba adjusted to post Soviet reality.

Who’s in charge?: The Castros. Fidel (84) handed over to his brother Raul (79) in effect in 2006 and formally in 2008. Fidel is a hardline Marxist and a follower of the Soviet model. He can be pragmatic at times but he doesn’t often compromise, and his enormous personal following means that he can rule almost single-handedly. Raul is by no means less hardline but he doesn’t have nearly so strong a personal following (putting it politely, he is really boring) and so he rules more consensually – relying on the advice of other senior communists such as: Carlos Lage Dávila (until his fall), José Ramón Balaguer Cabrera, José Ramón Machado Ventura, and Esteban Lazo Hernández. All these – apart from Ventura – are moderates.

As a result Raul’s regime started off on a considerably more moderate footing than Fidel’s, reforming import and export laws and making efforts to normalise relations with the USA. This coincided with a period in which Fidel was very sick indeed and played little role in the politics of the country. However of late Fidel has been feeling better and so has been taking a more active role in the politics of the country. This has resulted in a swing back towards the hardline position. There was confirmation of this in 2009 when Dávila lost his position and power after resigning following some oblique criticism from Fidel; and was further confirmed later in the year when the hardline Ventura was elected as VP. It is not entirely clear what will happen after the Castros die as the new concentration of power around the brothers and Ventura (80) doesn’t leave much room for a new government to emerge.

The Communist Party of Cuba has a very bureaucratic structure, and doesn’t make changes often. The chief secretaries (the Castros) and the 20 person Politbureau are elected at infrequent congresses, held on average every six years. There is to be a congress in April of this year – the first for 14 years – and this may produce a new ruling cadre.

There are a number of other political parties active in Cuba, although as all elections in Cuba are non-partisan they can never hope to achieve power. The CDRs view membership of these parties with suspicion and so many people do not wish to take the risk of joining. The largest of these parties is the Christian Democratic Party of Cuba, who campaign as Christian Democrats but oppose US foreign policy and any attempt to overthrow the Communist regime. It is not clear how big the party is, but it is not large and its leaders are in exile.

Other parties include the social democrat Cuban Democratic Socialist Current, the socialist pro-democracy party the Democratic Social-Revolutionary Party of Cuba, it’s illegal breakaway the Social Democratic Co-ordination of Cuba, the liberal Democratic Solidarity Party, and the illegal liberal Liberal Democratic Party.

Another movement, albeit a totally illegal one, is the Valeria Project (mentioned a couple of times above). It started off as a religious movement amongst Christians and soon became a major movement for the restoration of democracy. It is openly admitted that the project received a lot of support and funding from the USA – mostly from private citizens but also some backing from US ambassadors. However it is, as far as we can tell, indigenous in its genesis.

It is not clear how large it is, but its strongest moment was probably the collection of the 11,000 signatures to force a referendum in 2002. Following that the movement was heavily cracked down upon and most of its leaders are now in jail.

Another powerful force in Cuba is the Catholic church. Cuba is officially atheist, but restrictions on the church were dropped in exchange for a papal visit in 1998 and the church still has quite a following.

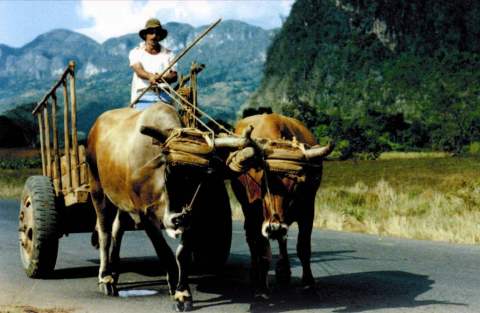

What does it look like?: It’s really pretty: hot but lush. There are flat rolling plains leading up to a backbone of fairly severe mountains, particularly in the east. A lot of the buildings are very old fashioned, and a lot of the cars are straight out of the 1950s – a result of the USA’s trade embargo.

What are the issues?: Cuba has many of the strengths and weaknesses you would expect from a heavily centralised state. Literacy rates are amongst the highest in the world and the healthcare system is one of the best on the planet (in part because preventative medicine is so strong, enforced as it by doctor’s ability to interfere in individuals’ lives in ways that would not be tolerated in a less totalitarian state). However poverty is rampant and manufactured goods are scarce. How to liberalise, and if to liberalise is the key question; as is the linked issue of relations with the USA.

A good source of impartial information is: Debate around Cuba is deeply polarised and it is very hard to get impartial information. Domestically this is perhaps unsurprising given the revolutionary history and uncompromising regime. What is disappointing is that the wider world seems to be incapable of being objective either. The problem is that Cuba has become a cause celebre for all sides. The left, and all those who find capitalist hegemony depressing (and lets face it all hegemonies are depressing), want an example of some other system of government working and so tend to overstate the case for Cuba as a successful alternative and paper over the regime’s flaws. Meanwhile many object to Cuba’s cute and fluffy image and point to its authoritarian leadership and human rights abuses – but they too tend to overstate the case.

The English language voice of the regime is the Cuban Granma and the external Cuba Si. The standards of journalism (objectivity aside) are pretty good and as propaganda it is very persuasive. It makes an eloquent case for the positives of the regime. However that which it passes over in silence, speaks volumes.

On the anti-Castro side the best I’ve found are The Real Cuba blog (currently down, but you can access a cached version) and A letter from Cuba. They are very good too and eloquently document the sins of the regime, but the tone is somewhat shrill.

A good book is: one of my favourite books is about Cuba: The Old Man and the Sea. It won’t teach you much about politics. For that you’re best off getting a good biography of Castro. Guerrilla Prince: The Untold Story of Fidel Castro

, Fidel: A Critical Portrait

, and Cuba Or The Persuit Of Freedom

are thought to be amongst the best. All are said to be reasonably balanced, the first two come down against him and the third in favour. Guerrilla Prince is probably the lest objective but gives fascinating insights into the Machiavellian ploys he has used to retain power.

The next elections are: Of more interest will be the Communist Party Congress in April. Municipal elections will be next held in 2013.

demotivator…

[…]Cuba « Who rules where[…]…